The Remarkable Shift in China's Attitude Towards Science

Written on

Chapter 1: The Cultural Revolution's Legacy

In recent years, I have been captivated by the television adaptation of "The Three-Body Problem," a novel I purchased from a street vendor in China many years ago. At that time, this work faced indifference and criticism from the public for its challenging views on intellectuals, scientists, and even Einstein’s theory of relativity—an experience that resonates deeply with those of us who lived through the Cultural Revolution.

For over twenty years, China was immersed in a period of derision towards Einstein and scientific progress, driven by a mix of ignorance and a misplaced sense of superiority, reminiscent of the Boxers who thought they were invincible against modern weaponry. While global advancements surged ahead, China found itself mired in superstition. It wasn't until 1978 that the nation recognized its deficiencies and began to cautiously embrace science and technology as crucial elements of productivity. During this transformative time, Deng Xiaoping boldly asserted that science and technology were not only productive forces but the foremost productive forces. Though this assertion appears commonplace today, it was a radical idea back then, facing significant opposition.

The transformation within a mere fifty years has been astounding. The outdated ideologies and mindsets of the past are unlikely to resurface. Historically, the left has been associated with anti-science sentiments.

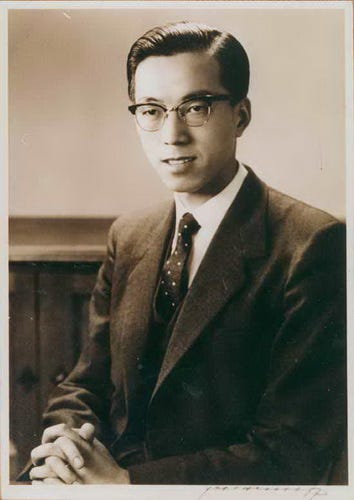

Yao Tongbin stands out as a prominent figure in the realm of aerospace materials and technology in China. His journey symbolizes the shift from a society that rejected science to one that values it. The past two decades saw concerted efforts in China to critique Einstein, fueled by ignorance and arrogance. However, as the world progressed, China began to confront its own backwardness, officially recognizing it in 1978. This acknowledgment ushered in a focus on the importance of science and technology for productivity.

Chapter 2: The Life and Legacy of Yao Tongbin

The first video, "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China," discusses how Deng’s policies paved the way for China's scientific advancements.

During this pivotal period, Deng Xiaoping's declaration that science and technology were not just productive forces but the cornerstone of productivity was revolutionary. This bold statement faced substantial opposition at the time. Yet, the rapid changes that followed rendered the outdated views obsolete.

The second video, "The Transformation of China," explores the broader implications of China's shift towards science and its global standing.

Yao Tongbin's life encapsulates this remarkable transition. He graduated from the Tangshan Institute of Technology in 1945 and later earned a doctorate in engineering from the University of Birmingham in the UK. In 1954, he was a researcher at RWTH Aachen University in West Germany, focusing on metallurgical and foundry studies. Returning to China in 1957, he joined the Fifth Research Institute of the Ministry of National Defense, contributing significantly to the establishment of the Institute of Materials and Processes, which became part of the Seventh Ministry of Machinery Industry, where he served as director.

However, Yao Tongbin's promising life was tragically cut short on June 8, 1968, during a violent clash between conservative and rebel factions. Aligned with the rebels, he became a victim of brutality, losing his life at just 45 years of age. In recognition of his immense contributions to aerospace materials and technology, the Chinese government posthumously awarded him the Two Bombs, One Satellite Meritorious Medal in 1999.

Yao Tongbin’s story epitomizes the evolution of Chinese society. His scientific achievements and sacrifice represent China’s advancements in science and technology. His legacy also serves as a cautionary tale, urging society to reject anti-science sentiments and embrace a forward-thinking approach to face future challenges.

As Lu Xun famously stated, "There is a man who is alive, and he is dead. Some people are dead, and he is still alive."