Exploring Capitalism and Socialism in Modern Transportation

Written on

Chapter 1: The Role of Transportation in Society

Transportation serves as the circulatory system of our communities. By examining it, we can delve into significant societal inquiries in our technologically advanced age.

In 1952, the renowned English mathematician and transport analyst John Glen Wardrop introduced two foundational principles governing route choice for vehicles in traffic. The first principle, known as user equilibrium, posits that no driver can shorten their travel time by altering their individual route. In simpler terms, at this state of equilibrium, travel times across all routes are identical. The second principle relates to social optimal travel, which emerges when drivers collaborate to minimize overall travel time. To illustrate this, let’s consider a practical example.

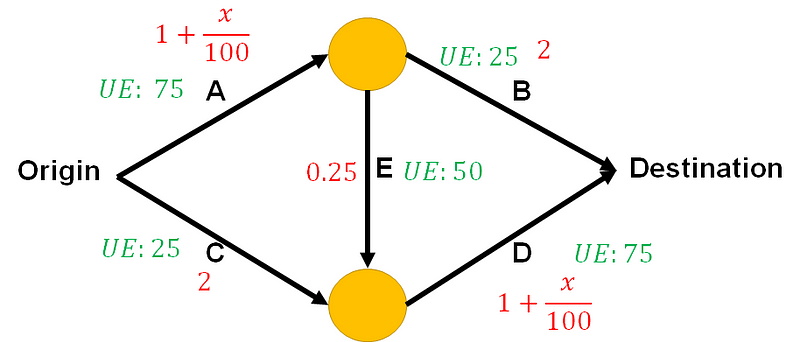

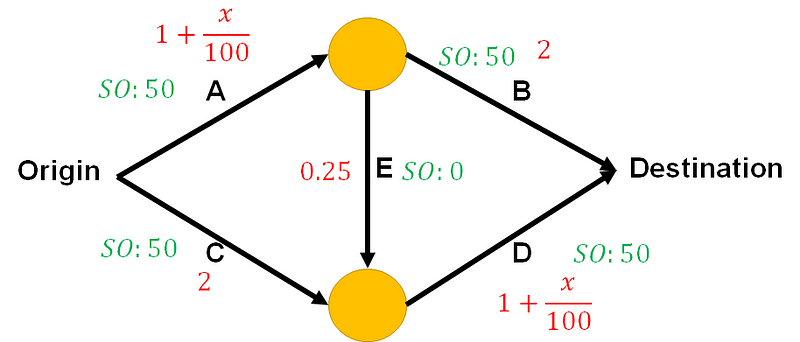

In the illustration above, we see three routes from Origin to Destination: AB, AED, and CD. The time taken on each route is expressed in minutes, with 'x' denoting the number of vehicles on that path and a total of 100 vehicles in this scenario. By equating the travel times across all three routes, we determine that each driver experiences a travel time of 3.75 minutes. Consequently, no driver gains from choosing a different route, which exemplifies user equilibrium. Yet, the question remains: is this the optimal outcome?

Surprisingly, the most favorable outcome occurs when path E remains unused. If drivers work together to avoid path E, the average travel time drops to 3.5 minutes for each driver! This phenomenon is known as Braess’ Paradox, where the elimination of certain routes can lead to improved travel times. However, a defector may still choose path E, and a growing number of defectors would push us back to the selfish user equilibrium. Clearly, perfect coordination yields better results.

Capitalist vs. Socialist Routing

Essentially, user equilibrium reflects a free market philosophy. Here, every driver has equal access to route information and ultimately selects the path that minimizes their own travel time or maximizes personal gain. The consequence? A less-than-ideal routing strategy. On the other hand, social optimality focuses on reducing overall travel times. While individual drivers might endure longer routes, the social optimal approach decreases total travel costs or enhances collective benefits.

So, how can society coordinate to achieve this minimal cost? Presently, the most effective traffic solutions are routing applications like Google Maps, which provide everyone with equal information and the best routes. This mirrors selfish routing, or user equilibrium. What if, instead, everyone received distinct routes aimed at maximizing social welfare by minimizing overall travel times? You might argue that you want to arrive at work punctually and are unwilling to sacrifice for others. However, if this game is played 261 times annually during your commutes, you could ultimately reduce your travel time! The growing use of big data technologies may soon help realize this vision.

In the near future, it may become feasible to synchronize routing and optimize transportation. This capability could prove invaluable during emergencies, such as hurricanes. For instance, during Hurricane Irma, traffic congestion extended from Florida to Tennessee—over 700 miles. Coordinated routing and information sharing could eliminate these evacuation traffic jams.

The Broader Societal Context

I perceive transportation as a stage for societal interactions. While transportation is intricate, it is less complicated than the intertwined complexities of society itself. The example of selfish versus social routing demonstrates that societal scenarios are not so straightforward. Although capitalism has generally served us well, it is evidently not the most efficient system. Why is this the case? Numerous additional complexities and minor disturbances can lead to significant emergent consequences. For instance, if a significant portion of society perceives socially optimal solutions as "evil" due to misinformation, any potential improvements will likely fail, regardless of their magnitude. Furthermore, the individual or group defining what is socially optimal may possess flawed judgment.

But how might big data and information transform our society? During the recent presidential election cycle, over $10 billion was spent—more than the GDP of Haiti! But do elections, which are ostensibly for the public, truly benefit from such expenditures on advertisements through TV, Google, and Facebook? Rather than pouring funds into these avenues, big data and scientific methodologies could enable us to objectively assess which policies yield greater societal benefits through comprehensive data collection. More resources could be directed toward effective policies instead of political infighting. However, this powerful tool carries the risk of misuse. The convergence of transparency, accountability, and big data could profoundly enhance society.

Chapter 2: Video Insights on Economic Systems

The first video, "Capitalism vs Socialism vs Communism," provides an overview of the fundamental differences between these economic systems, shedding light on their implications for society.

The second video, "Capitalism and Socialism: Crash Course World History #33," delivers a concise analysis of the historical context and impact of these economic ideologies, offering a deeper understanding of their roles in shaping modern transportation.