What Color Is Everything When Nobody Is Observing?

Written on

Chapter 1: The Nature of Color Perception

The way we interpret colors varies with different wavelengths of light. As Paul Klee once expressed, “Color is the meeting point of our brain and the cosmos.” But is the sky genuinely blue? Is white a blend of all colors? It appears that way, but this perception is constructed by our brains.

In educational settings, we learn that light consists of electromagnetic waves, and the specific wavelength of these waves dictates the colors we perceive within the visible spectrum. For those wishing to revisit this concept or delve deeper into the properties of light, I recommend checking out my article, "The Science of Light: The Heartbeat of the Universe."

The Science of Light: The Heartbeat of the Universe

A particle, a wave, an energy field—what exactly is light?

Here’s a refresher on what you might have encountered:

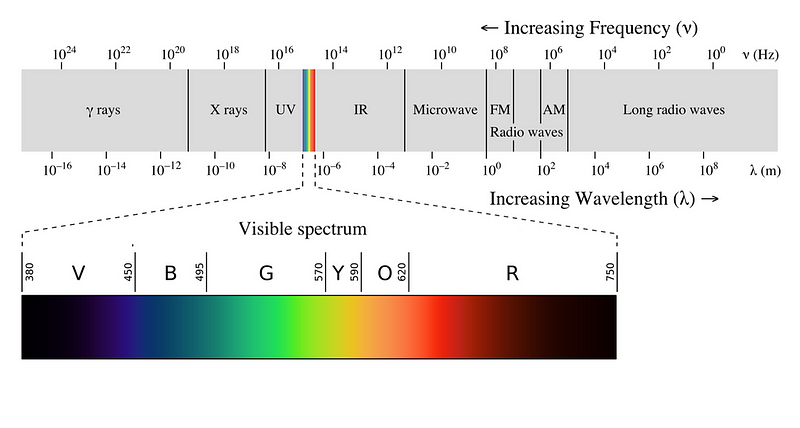

Electromagnetic waves exhibit various characteristics dependent on their frequency or wavelength—two aspects of the same phenomenon, given that the product of frequency (f) and wavelength (λ) is constant, specifically the speed of light (c). Only a minuscule portion of the spectrum is visible to the human eye, representing what we know as optical light; we cannot perceive microwaves or Wi-Fi signals.

Are Colors Real?

The wavelength of electromagnetic waves does not inherently possess color. It's our human sensory perception that transforms light into optical colors. If we assert that the wavelength determines the observed color, that's accurate. However, to understand the Universe beyond human observation, it’s crucial to recognize that light itself and its wavelengths do not possess intrinsic colors.

Thus, posing the question, “What color is the Universe when unobserved?” is akin to asking, “If a tree falls in an empty forest, does it make a sound?”

It is our human brains, along with those of other vertebrates, that fabricate the concept of color. In a sense, colors are not "real" in the objective way we often presume. They exist as a consensus among humans, and fortunately, no other species challenge this notion.

Understanding Color Perception

Electromagnetic waves travel from energy sources, and when they interact with matter, they are absorbed as quanta of energy, known as photons. While we know light interacts with familiar matter, there may be other forms of matter that do not interact with light, rendering them invisible to our senses. This is what we refer to as dark matter, but that topic is beyond our current discussion. For further reading, see "Gravity-Based Life As We Don’t Know It."

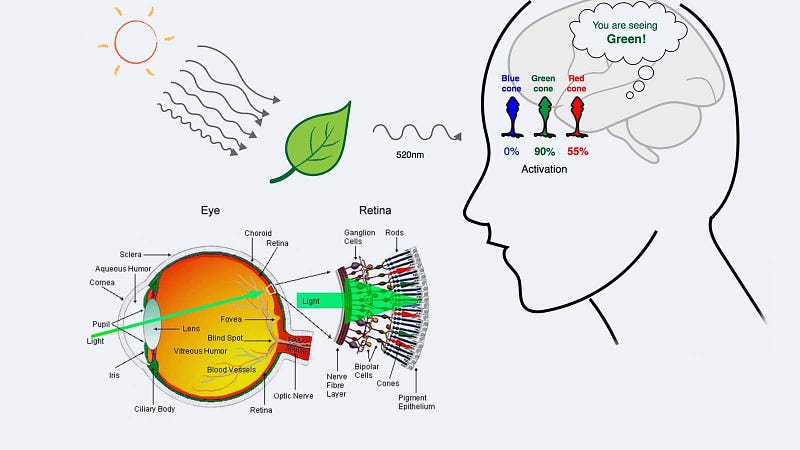

When electromagnetic waves enter our eyes, they may come directly from a source like the sun or a star, or they could be reflected after being absorbed by other materials.

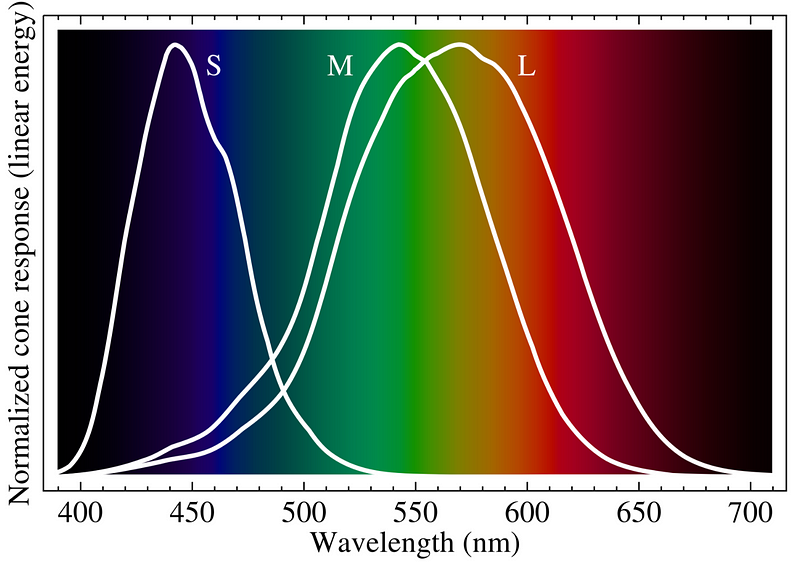

Once a photon is absorbed by our eyes, it travels through the lens to the retina, which contains rods and cones—the latter being responsible for color detection. Humans possess three types of cones, each attuned to specific wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, designated as S, M, and L. These cones relay information to the brain about the activation levels of each type.

The wavelengths themselves do not correspond to specific colors until the brain assigns them such labels. For instance, if 10% of S-cones, 90% of M-cones, and 10% of L-cones are triggered, the brain interprets this combination as green, corresponding to wavelengths around 540 nm.

Thanks to these cones, we can detect wavelengths roughly between 400 and 700 nm. Other species exhibit varying types and quantities of cones. For example, dogs have two types of cones (for blue and yellow), resulting in dichromatic vision, but they possess more rods for superior night vision. Conversely, cats also have three types of cones but in fewer numbers, leading to less clarity yet broader peripheral vision due to their eye structure. They also excel in low-light conditions due to a greater number of rods.

Birds, with their relatively large eyes and specialized muscles, have four types of cones, including one that detects ultraviolet light, enabling them to see colors beyond human perception. The mantis shrimp takes this even further, boasting 12 to 16 types of cones and the ability to perceive different light polarizations. Capturing the essence of their visual experience is challenging, but efforts have been made to visualize color polarization through specialized cameras, as seen in the video below.

The Subjectivity of Colors in the Universe

Thus, colors are a construct of biological interpretation. They are not inherent properties of the "objective Universe." We assign colors to celestial bodies, rendering stars yellow, sunsets purple, and nebulae blue.

When observing a colorful nebula and questioning whether those colors are authentic, or comparing different renditions of a nebula, remember: the answer hinges on the observer's perspective and the filters applied during observation.

Images like the one above are captured using various broad- and narrowband optical filters to isolate specific wavelength absorptions, resulting in black-and-white images that are subsequently colorized. Thus, the coloration of celestial objects can vary based on the techniques employed.

Evolutionary Aspects of Our Senses

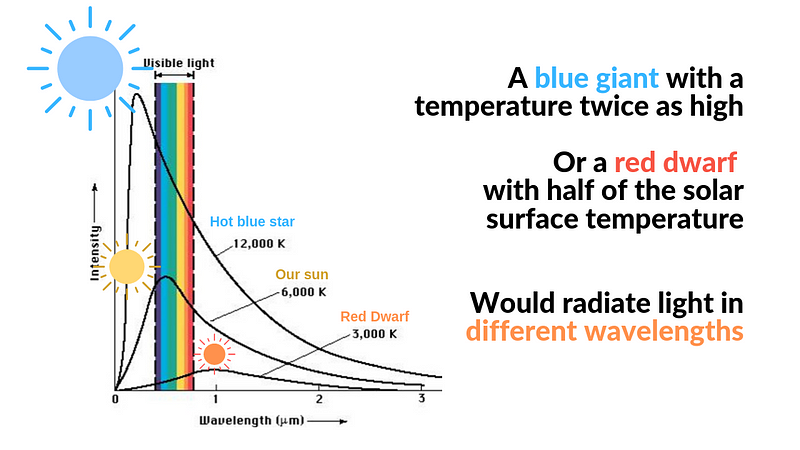

Our vision has evolved alongside our species on Earth. The visible spectrum we interpret as light is ideally suited to the wavelengths emitted by our primary energy source, the Sun. Had we evolved on a different planet orbiting a star with a distinct temperature and radiation profile, our visual spectrum would likely differ.

Even on Earth, numerous life forms don’t rely on vision as their primary sense. For instance, bats navigate their environment through echolocation.

Considering extraterrestrial life, if they inhabit a star unlike our Sun, their visual experience would likely differ from ours, even if they relied on vision. Additionally, other vertebrates exhibit slight variations in wavelength absorption tailored to their visual needs.

As we ponder the potential for human evolution into a galactic species, we might wonder how our sensory perception would adapt on a cosmic scale.

Conclusion: The Reality of Color Perception

What color does the Universe manifest when unobserved? In reality, the Universe lacks color. It contains electromagnetic waves, but it is ultimately our brains that assign colors to specific wavelengths.

We cannot fully comprehend how other species, like birds or mantis shrimp, perceive their worlds. Their experiences are shaped by their unique physiological structures and how their brains interpret electromagnetic signals.

In essence, colors exist solely in our minds; they are not objective characteristics of the Universe. Assuming the Universe exists independently of our interpretations (ontological realism), the reality of color remains a complex subject.

Yet, considering that all our senses derive from the electromagnetic force, one might wonder: Could we envision perceiving the Universe through entirely different forces?